Power to the Patients

Alison Anderson thought she had beaten cancer. Diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer in 2008 at the age of 38, she underwent the standard therapies for a woman under 40 with stage I disease and had done well.

But in 2012, during her third pregnancy, she developed a persistent backache. At first, she didn’t worry about it, and treated it with massage and acupuncture. Then, the pain migrated to one of her ribs. Unbeknownst to Anderson and her doctors, her original cancer had spread to her bones. It had been resistant to her earlier treatment. “We were completely blindsided,” Anderson said of her eventual diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer.

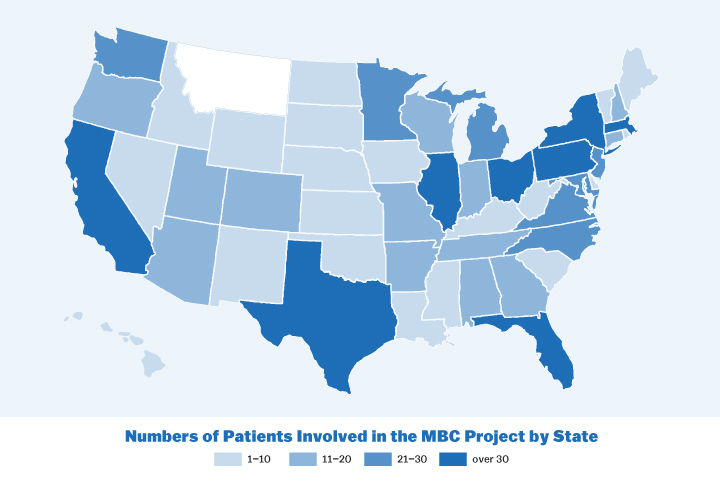

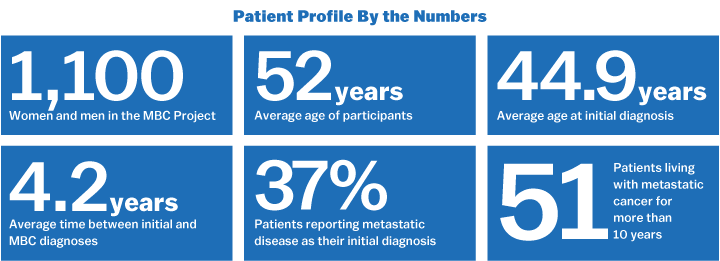

Like many patients facing metastatic cancer, Anderson felt helpless. But the Houston-based mother of three has found strength in the metastatic breast cancer community, and is now one of more than 1,100 women and men across the country taking part in an ambitious patient-driven genomic research project based at the Broad Institute. Although they may not benefit directly from the project, these patients are committed to helping researchers solve their disease and develop future treatments.

Alison Anderson and her children Avery, Evan, and Grace

Alison Anderson and her children Avery, Evan, and Grace

Called The Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC) Project, the initiative tackles one of the biggest challenges in cancer research: tumor samples and medical information from the vast majority of cancer patients aren’t available for scientists to study, because most patients are not cared for at the major academic centers where this research is conducted. But, a few years ago, Broad Institute researchers thought these geographical and other barriers could be overcome by a tool many U.S. patients had access to: social media.

Nikhil Wagle, an associate member at the Broad Institute and oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, envisioned a direct-to-patient initiative that would recruit cancer patients through Twitter and Facebook. In turn, these patients would volunteer their clinical information and access to their tumor samples, which would be sequenced at the Broad. When he ran the idea by local patients and advocacy groups a year ago, their response was enthusiastic. Catalytic philanthropy from an anonymous donor enabled Wagle and his team to turn this bold idea into reality.

Metastatic breast cancer is an ideal test case. First, there is an urgent—and unmet—need to conduct more research. 40,000 people succumb to the disease annually in the United States, and the life expectancy is a mere three years. “There really isn’t a cure,” Anderson said. “Once the cancer becomes metastatic, we’re just dependent on therapies to extend our lives.”

Another compelling reason is the strong community among metastatic breast cancer patients and advocates, including support groups and online forums. Over the course of several months, Wagle and Corrie Painter, the project’s associate director of operations and scientific outreach, connected with these communities over social media and collaborated with patients to design every step of the patient experience in the MBC Project.

“We wanted to build it in lock-step with the people who are the biggest stakeholders—the patients with metastatic breast cancer,” said Painter, who is not only a trained cancer scientist but also a cancer survivor and patient advocate. She continues to brainstorm with a number of patients and advocates about the project's next phases.

The result is this website, where metastatic breast cancer patients can click “Count Me In,” enter their email address, and fill out a short optional 15-question survey. The questionnaire covers basics like zip code and age and more detailed information about treatment history. The researchers then use that information to identify patients who “give us the greatest likelihood of making discoveries that could help the most people with metastatic breast cancer the fastest,” Wagle said.

To begin, the project will focus on patients with extraordinary responses—those who do especially well with treatment. (More than 50 MBC Project participants have lived with the disease for more a decade.) The rare patients who are diagnosed with metastatic disease from the start form another key part of the study. Eventually, Wagle also hopes to study genetic risk factors for younger patients and differences among ethnic groups.

After filling out the online survey, patients submit consent and release forms providing access to their medical history, and provide a saliva sample for comparison to their tumors. The MBC Project scientists contact the hospitals where the patient has been treated to obtain tissue samples for sequencing.

Doctors, too, can get involved. To help patients and other physicians spread the word, the MBC Project provides an explainer for oncologists on its website. As the results come in, the scientists will make a concerted effort to share the data widely with researchers and will also share aggregated data with patients. In addition, the project’s team hopes to recruit even more diverse patient populations with offline outreach.

Already, the project is sowing hope for patients like Anderson, who is grateful to have the chance to make a future impact. “I want my DNA and my cancer to be involved in this study because it’ll save lives down the road,” she said.

“I feel like I’ve been given some level of control over my destiny by being able to participate,” she added. “For me, the MBC Project means life and death.”