Beating Back Cancer Drug Resistance

Levi Garraway, an oncologist, used every technique in the precision medicine toolkit to treat his lung cancer patient. He sequenced the man’s tumor, identified a genetic mutation with a matching drug, and used the treatment to stabilize the patient’s condition. Eight months later, however, the tumor came roaring back to life.

“It’s humbling,” said Garraway, an institute member at the Broad and physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “Some patients benefit greatly from precision medicine approaches, but there are still a lot more who do not. And resistance is a huge problem with every current cancer drug.”

Drug resistance has confounded cancer researchers since the 1940s, when medical pioneer Sidney Farber began finding effective drugs against childhood leukemia. We now know that deep within the tumor, a small population of cells manages to escape the initial treatment. These cells acquire changes over time that allow them to continue to grow successfully, even in the presence of drugs. The patient relapses, with a cancer that is even deadlier.

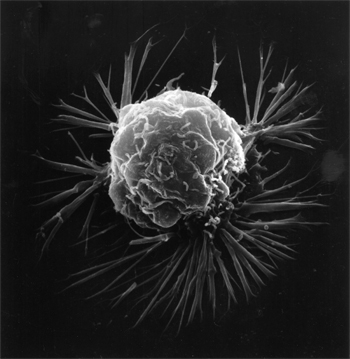

A breast cancer cell

A breast cancer cell

Scientists still don’t know all the mutations and pathways that lead to drug resistance. But researchers at the Broad, with the generous support of the Gerstner Family Foundation, aim to fill this critical need. “For the first time, we have the power to understand the details of how cancer drug resistance works,” said founder Louis V. Gerstner, Jr., who is also chairman of the Broad’s board of directors. “There’s a lot of work to do, but we believe that the Broad can lead the way and figure it out.”

With this philanthropic partnership, a team of Broad researchers has now launched a two-pronged initiative to tackle this task. Aided by technological advances in genome editing and sequencing, they will systematically and comprehensively identify the mechanisms of drug resistance for the first time. In the laboratory, Broad scientists are using the CRISPR genome-editing tool to rapidly test which genes are responsible for cancer drug resistance.

At the same time, a path-breaking study is taking place in the clinic. The Broad is teaming up with two of the world’s leading cancer centers—Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center in Boston and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York—to launch the largest genomic study of patients’ pretreatment and post-resistance tumors. The study—led by Garraway and José Baselga, the physician-in-chief and an oncologist at MSKCC—also aims to identify the mutations that cause resistance by comparing the genome sequences of pretreatment tumors and resistant tumors.

Since the project’s start in the summer of 2015, the team has enrolled 46 patients with advanced lung or breast cancer. Already, it’s clear that the researchers are gaining valuable information from the extra biopsy sampling. “The data thus far has provided some highly relevant insights into how resistance may arise. In some cases, those insights could make an impact on clinical care—something we didn’t expect to see this early in the study,” Garraway said.

Levi Garraway, M.D., Ph.D.

Levi Garraway, M.D., Ph.D.

The patients are also leading the way towards a revolutionary new biopsy method that would be far less invasive than traditional biopsies: “blood biopsies.” Part of the reason multiple biopsies have been rare in the past is their cost and difficulty. To circumvent this problem, another team of Broad scientists is using blood samples taken from all the enrolled patients at DF/HCC and MSKCC to improve techniques to isolate and study tumor cells and cell-free genetic material found in a patient’s bloodstream.

“The blood biopsies are already starting to yield information that suggest we could use them to study and understand resistance going forwards,” said Nikhil Wagle, a physician-scientist and oncologist involved in the research.

In the meantime, Viktor Adalsteinsson, a leading scientist on the project, has set up an automated pipeline to handle and track samples from the clinic through to sequencing and analysis, allowing both lab researchers and clinicians to see how far a given sample has progressed. This automation has sped up analysis five to tenfold, he said. With access to between 50 and 100 patients for analysis each month, “we’re at the point where we can really begin to uncover some exciting biology from circulating tumor cells and cell-free DNA,” he added.

Adalsteinsson highlights the role of philanthropy in propelling the project forward. “The Gerstner Family Foundation gift has enabled us to take our blood biopsy work to the next level and try to apply it to a much larger number of patients,” he said.

Garraway agreed. “It takes a lot of money to collect, generate, and analyze this data,” he said. “But there is presently no federal mechanism to do this kind of study. Without the Gerstner Family Foundation, we wouldn’t have been able to get this off the ground.”